DESIBUZZCanada

Events Listings

Dummy Post

International Day Of Yoga To Be Virtually Celebrated Saturday At 4pm

CANCELLED: Coronavirus Fears Kills Surrey’s Vaisakhi Day Parade

ADVERTISE WITH US: DESIBUZZCanada Is The Most Read South Asian Publication Online

SURREY LIBRARIES: Get Technology Help At Surrey Libraries

WALLY OPPAL: Surrey Police Transition Update On Feb. 26

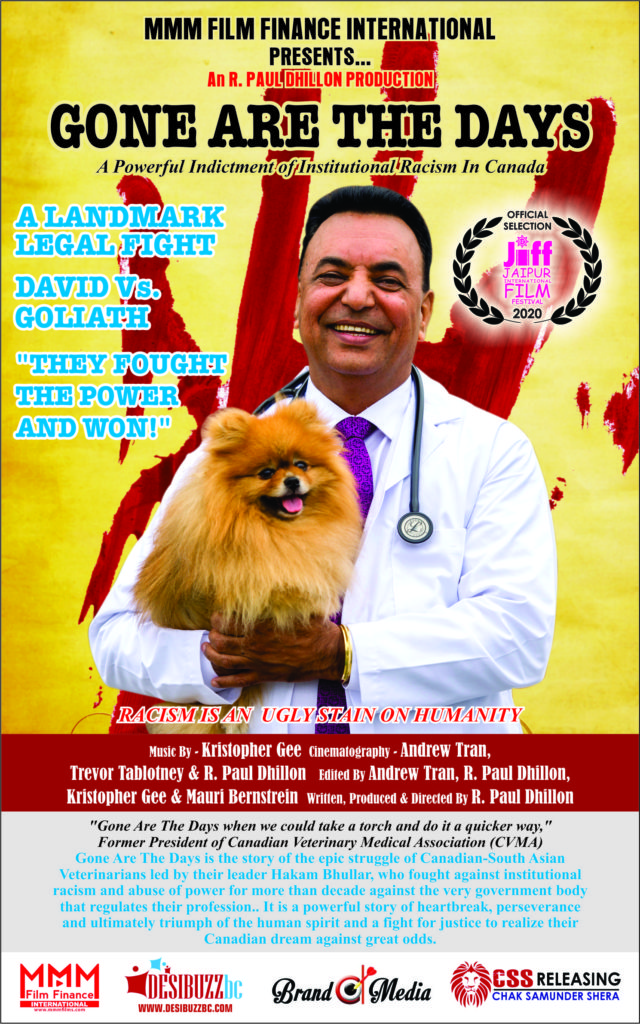

GONE ARE THE DAYS - Feature Documentary Trailer

Technology Help At Surrey Libraries

Birding Walks

Plea Poetry/short Story : Youth Contest

International Folk Dancing Drop-in Sessions

A CONVERSATION: Extraordinary Author-Poet K.K. Srivastava Talks About His Work And Career

- March 18, 2020

By Ashok Bhargava

Author-Poet K.K. Srivastava is an accomplished professional with a Masters in Economics from Gorakhpur University in 1980, who joined the Civil Service in 1983.

Srivastava has written three volumes of poetry: Ineluctable Stillness (2005), An Armless Hand Writes (2008; 2012) and Shadows of the Real (2012), his poems have been translated into Hindi (Andhere Se Nikli Kavitayen—VANI PRAKASHAN (2017) and his book Shadows of the Real into Russian by veteran Russian poet Adolf Shvedchikov. His fourth book Soliloquy of a Small Town Uncivil Servant: a literary non-fiction was published in March 2019 by Rupa Publications, New Delhi. Currently he is working as Additional Deputy Comptroller and Auditor General in the office of Comptroller & Auditor General of India.

Ashok Bhargava, an eminent poet and President of WIN (Writers International Network) Canada sat down with Srivastava to talk about his books and other related issues. Here are the excerpts from the interview.

Ashok Bhargava- When did you get the initial urge to write? Were you prompted by some inner force to write or did external stimuli put pressure on you?

K K Srivastava (KKS) - I belong to Gorakhpur but as luck would have it, I got my first posting in service in 1987 to the then Pondicherry; roughly 3000 kilometers away from Gorakhpur. Obviously a sense of alienation gripped me throughout. I must admit it was one of the two most enjoyable postings I have had. The second being the then Trivandrum from 2014 to 2017. These two places gave me alienation which in turn gave me the road to travel alone. On such a journey, I chanced upon laying my hand on William Blake’s poem ‘Infant Sorrow’. What a poem it was! It taught me about dark connections between a mother’s womb and a child’s limping out of it and it also gave me my first poem in 1988: ‘Birth Trauma’. Pessimism ran through the poem but truth never gets dethroned from pessimistic outpourings.

Ashok Bhargava- Then. What about further writings? You have almost had thirty years of writings with you.

K.K.S- While I still was in Pondicherry, I read Eliot’s and Muktibodh’s longer poems: The Waste Land, ANDHERE MEIN and BRAHAMARAKSHAS respectively. Through these poems, I started learning the art of thinking. Only that. Eliot’s The Waste Land and Muktibodh’s two poems I mentioned above went very well with me. I realized the value of aloneness and how thoughts get born in those tormenting moments of loneliness. Next ten years or so I devoted to reading: serious reading of absurd literature particularly, Kafka, Camus, Borges, and Nietzsche. Fraud was replaced by Carl Jung. Carl Jung’s book Essays on Contemporary Events, in particular, influenced me the most. Things were getting firmed up in my unconscious mind and the haze of hesitation began to evaporate. My first poetry book INELUCTABLE STILLNESS came in 2005. I was excited to see the proof sent by the publisher. Reviews were difficult. It was first book and that too a poetry book. The first brief review came in Hindustan Times, Ranchi edition in 2005 where the reviewer wrote this, ‘He is not a genteel poet, he is a disturbing poet, intent on unraveling the human mind of its false preconceptions, of its delusive hypocrisy masked as genuine emotions.’ This assessment amused me. A year later Bernard Jackson a British poet and Patricia Prime from New Zealand wrote fairly exhaustive reviews. AN ARMLESS HAND WRITES was published in 2008 and in literary circles of poets it got some more attention. The book got reviewed by scholars like Kurt F Svatek of Austria and Stephen Gill of Canada. Third poetry collection SHADOWS OF THE REAL had the blessings of internationally celebrated poet Jayanta Mahapatra (known for his reclusive nature) who wrote Foreword to the book. Most importantly this book facilitated my fourth book: a literary non-fiction SOLILOQUY OF A SMALL TOWN UNCIVIL SERVANT. Many critiques in established newspapers/magazines are available on Google. I need not belabor further.

Ashok Bhargava- I find from your books about your reading. It must be consuming lot of time. Do you miss out something or do you lack something you wish you could not have?

K.K.S- Can I ask you a simple question? Is creativity a normal thing; a common art available to each and every individual? Of course not. For fairly long time writers pay a price in terms of their sense of seclusion. Creativity is taxing: it taxes on your brain, your imaginative skills, your intelligence and above all it weighs your mental tolerance. Writers resorting to opiating drugs, heavy bouts of alcohol, ending off and on in mental asylums is not a rarity. See the chequered history of writers and poets like Virginia Woolf. Edgar Poe, Ezra Pound, Sylvia Plath and many more. Coming to myself, fortune has not led me to knock at the doors of abovementioned succors. Future holds no guarantee. Past I don’t lament

Ashok Bhargava - Please elaborate, ‘Past I don’t lament.’

K.K.S- I don’t believe in flattering those who matter, networking, wining and dining in late night parties amidst purposeless guffaws and slanderous tales by people whom critic and poet Jeff Gundy fondly dubs as ‘ruined stoned walls’. Theses ‘ruined stoned walls’ must bear one thing in mind: Divinity watches and punishes: it just halves either before or after. In retrospect I missed nothing nor ever do I feel I lacked something. My goggle profile amazes me: a man from a small town with humble beginnings.

Ashok Bhargava - Perhaps that may be the reason Professor Jonah Ruskin-Professor Emeritus at Sonoma State University wrote about your fourth book in New York Journal of Books, ‘one might think that Srivastava was a French existentialist writing about alienated civil servants in France.’

K.K.S- Professor Ruskin, being a learned, experienced writer must have drawn this conclusion from his reading of the book. I admire his deep insight. Incidentally Patrick J. Sammut, a Maltese poet and critic too said more or less similar things in his incisive review in Indian newspaper The Pioneer. He expanded on various implications of being an ‘Uncivil Servant’.

Ashok Bhargava - With your fourth book you took a departure from poetry. What prompted you to go to prose? What desire? I mean.

K.K.S- I was propelled by a desire to tell my stories telling which was too difficult through poetry. Soliloquy is my story, about myself, about those I interacted with or those who interacted with me. Poetry suffers limitations in terms of telling stories though there is a criticism that T. S Eliot’s The Waste Land was his autobiography. Poetry has limitations. Perhaps that limits readership. You need intelligent readers with patience to understand poetry. Prose offers better narratives and lesser intelligent people can also handle prose.

Ashok Bhargava - Prorogue is beguiling and compelling when one reads it with preceding Michel McClure lines, ‘We are huge figures at small doors/of caves looking into blur/we rub selves against what is not there/and laugh and cry out.’ Very meaningful lines, indeed. Your views?

K.K.S- Certainly. Prorogue defines what lies beneath. Actually I wanted to put a crucial passage regarding Kohler’s ‘Mentality of Apes’ and unreal people mimicking that mentality but the book editor brushed aside the idea on the ground of losing readers. I succumbed to her arguments. I eulogize McClure’s poetry. He is clear, blunt and no holds barred type. His impact runs throughout my fourth book: it is all about not yielding to pressures from your inferiors. The moment you yield to your inferiors, you lose your stature as a writer. Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz leaves the issue of how much risk a writer wants to take through his writings to that writer himself. And Mahfouz does not want others to justify a writer’s risk. Just like a writer relishes risks his works entail, I do too.

Ashok Bhargava - I find Chapter 5: ‘Sex and Sensuality’ difficult to understand in terms of where you begin, how you proceed and how it ends. It arouses interest but as a reader I find complexities in relationships. You make love a complex issue.

K.K.S- One reason I appreciate your observations is this. First four chapters are more or less based on facts I have been confronted with directly. So absorption by readers is easy. ‘Sex and Sensuality mixes met desires with desires unmet. Both Carla D. and Miss X are real. As a writer I have duties towards readers and my characters. A writer’s characters come from very real, visible world; and his imaginative world creates camouflaged characters. Camouflaging is determined by how much a writer reveals the unreal part and how much he conceals the real part. Death and love are the most complex things in life: I have already encountered the latter; the former I will encounter one day as all do.

Ashok Bhargava - You write in chapter titled ‘Social Media’ and I quote, ‘Reality is a dream. By the time you realize it, half of your life has been lived and you are not sure if the other half left over, belongs to you at all.’ How is social media related to this statement; the first sentence of this chapter?

K.K.S- Social media is like mirror which displays society’s face to it. True face needs to be displayed. One rushes to social media as real life has gaping holes that real life tools can’t fill. Real life is never a complete life; it has to yield to many things unnatural. At the same time it does not yield to many things natural. Sometimes I am aghast at people outpouring their words of wisdom at weird hours of night on whatsApp or Fb or other modes of social media. So society is agile throughout 24X365 days. That’s a good symptom of an awake society. But then next question is: what for? Are you not rushing there to have your unmet desires met? Unfulfilled hopes yearn for a solution through social media. Edward Hamilton writes,’…he could look up and see the wind/ made physical by the sand it carried.’ Social media’s role is exactly this. It carries the sand through which physical existence gets visible to viewers/readers. The sentence you quoted from my book is about the quality and quantity of the sand social media confronts its readers with.

Ashok Bhargava - You look at the history of literature, particularly poetry. There are many issues involved in the act of literary writings. Can you enumerate a few? Do personal reminiscences in literature render imagination a weak business?

K.K.S- People have taken their lifetime to make out what they expect from a piece of writing. As a reader you keep riding out manifestos and arguments sponsoring one school over the other. When a reader praises one poem or literary piece, he faces a number of questions that have a bearing on your questions. Like: Does deep imagery leave a lasting effect? Does lyricism succumb to narrative? Was ‘confessional’ poetry a means to explore universal themes of human conditions? Turning to your question regarding self, Is construction and portrayal of self a legitimate objective? Works of Louise Gluck and Frank O’Hara are indicative of their being aware of dangers of an objective rendering of the self. I agree writings about self are limited by shrunken imagination which, in my view, inhibits the documentation of dynamics of change at a more enhanced plateau. The literature of today is in dire need of portrayal of actual images of fast changing societies rather than the ones accruing from accumulated imaginations flourishing on transcendence. Societies you see are authentic ones; your own self that you see may not be authentic but as Frank O’Hara reiterates, it is ‘a way of staying new.’ Self-intrusion in modern literature mars true literature. Cool detachment of a writer enables him render true literature which helps in settling societies. Societies, world over, need writers’ tiny help in getting settled.

Ashok Bhargava - Your publisher describes you as ‘reclusive and reticent.’ Do these attributes help you in your writings?

K.K.S- Yes, these do. Reclusiveness makes time available to me. Reticence makes me hear otters. I am a keen listener of how and what people talk, how they laugh and how they gaze. This combination of ‘reclusiveness and reticence’ makes a writer worth his salt. I avoid participation in talks that are mentally tiring, sexually lewd and intellectually unexciting. For me, apart from my office work which, of course, merits first priority, my family is there. Then, reading and writing demand a lot of attention, alienation and experimentation. Where is time for networking, dicing and drabbing, partying, weekend’s get-togethers at one of the coterie’s member’s house by rotation where ‘significant policy decisions and their own and others’ career progressions’ are deliberated upon to be implemented as planned, and a host of similar detours? Almost all writers shun social gatherings. If someone considers it as a symbol of weirdness, so let it be. Yeah. I remember Dante. See his response to a question someone posed to him. ‘Why it is so people prefer buffoons to you.’ Instantaneously came the reply from Dante, ‘Like likes like.’ You know writers respond either instantaneously or decades later.

Ashok Bhargava - What you expect from you as a writer when you write? Any pursuance of objective?

K.K.S- I abhor mediocrity: be it in real life or literary life. I was reading Montaigne’s ‘Of Experience’ where he argues that ‘popular opinion is wrong; it is much easier to go along the sides…….middle way, wide and open.’ I interpret Montaigne’s above line as assuming a hallway rather than a mountainside path. But it that case too there is solid edge to hold to. Self-analysis, for me in my writings is a must, though via these discursive forays I seek style and discipline in writing. Many writers go for flexibility and adaptability but then I treat these as symbols of mediocrity. Muddling meddlers don’t bewitch me. I have my ideals in writers like Nirad C. Choudhury, V.S Naipaul and Salman Rushdie who leave the element of ‘self-risks’ in the dustbin before they start writing a book.

Ashok Bhargava - Last question. What about your next book? Can you tell something?

K.K.S- I am afraid I can’t excepting I am at it and it is about very real characters and circumstances that have come my way in my real life. The history of yesterday can be the story of tomorrow. My next book will be an authentic book of tomorrow based on authentic history of yesterday. Thank you.

About the Interviewer:

Ashok Bhargava is a multilingual poet, speaker and essayist. He is an avid volunteer, supporter & organizer of various social and artistic activities. He is the founder of “WIN – Writers International Network Canada.” He has been featured on CBC Radio (Sounds like Canada & North by Northwest) and Chanel M TV.